In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

My mission in this column is to look at older books, primarily from the last century, and not newly published works. Recently, however, an early and substantially different draft of Robert Heinlein’s The Number of the Beast was discovered among his papers; it was then reconstructed and has just been published for the first time under the title The Pursuit of the Pankera. So, for a change, while still reviewing a book written in the last century, in this column I get to review a book that just came out. And let me say right from the start, this is a good one—in my opinion, it’s far superior to the version previously published.

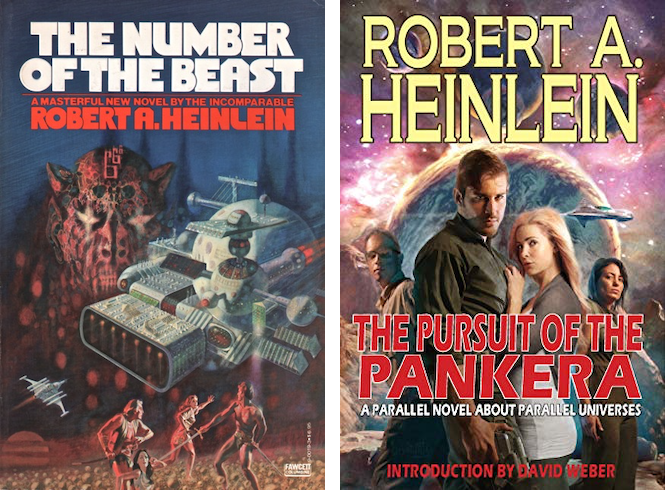

The Number of the Beast first appeared in portions serialized in Omni magazine in 1978 under the editorial direction of Ben Bova. Bova had recently finished a stint editing Analog as the first editor to follow in the footsteps of John W. Campbell. Omni published a mix of science, speculation on parapsychology and the paranormal, and fiction; a slick and lavishly illustrated magazine, it unfortunately lasted less than twenty years. The book version of Heinlein’s novel was published in 1980. My copy is a trade paperback, which was a new format gaining favor at the time, gorgeously illustrated by noted artist Richard M. Powers. While the cover is not his best work, the interior illustrations are beautifully done.

No one knows exactly why Heinlein abandoned the original version of his book, although that version draws heavily on the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs and E. E. “Doc” Smith, and there may have been difficulties in gaining the rights to use those settings.

On my first reading of The Number of the Beast, I was excited by the prospect of reading a new Heinlein work, but also a bit apprehensive, as I had not generally enjoyed his late-career fiction. Where Heinlein’s earlier published works, especially the juveniles, had been relatively devoid of sexual themes, the later books tended to focus on the sexual rather obsessively, in a way I found, to be perfectly frank, kind of creepy. I remember when I was back in high school, my dad noticed that I had picked up the latest Galaxy magazine, and asked which story I was reading. When I replied that it was the new serialized Heinlein novel, I Will Fear No Evil, he blushed and offered to talk to me about anything in the story that troubled me. Which never happened, because I was as uncomfortable as he was at the prospect of discussing the very sexually oriented story. Heinlein’s fascination with sexual themes and content continued, culminating with the book Time Enough for Love—which was the last straw for me, as a Heinlein reader. In that book, Heinlein’s favorite character Lazarus Long engages in all sorts of sexual escapades, and eventually travels back in time to have an incestuous relationship with his own mother.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) is one of America’s most widely known science fiction authors, often referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Citizen of the Galaxy. Since I have a lot to cover in this installment, rather than repeat biographical information on the author here, I will point you back to those reviews.

The Number of the Beast

Zebadiah “Zeb” John Carter is enjoying a party hosted by his old friend Hilda “Sharpie” Corners. A beautiful young woman, Dejah Thoris “Deety” Burroughs, introduces herself to him, and they dance. He is impressed by her, compliments her dancing and her breasts (yep, you read that right), and jokingly proposes marriage. She accepts, and while he is initially taken aback, he decides it is a good idea. Deety had wanted Zeb to meet her father, math professor Jacob “Jake” Burroughs, who had hoped to discuss math with Zeb, but it turns out that the Burroughs had confused him with a similarly named cousin. The three decide to leave the party, and on a whim, Hilda follows them.

As they head for the Burroughs’ car, Zeb, a man of action, has a premonition and pushes them all to safety between two vehicles, as the car they were approaching explodes. Zeb then shepherds them to his own vehicle, a high-performance flying car he calls “Gay Deceiver,” and they take off. Zeb has made all sorts of illegal modifications to the air car, and is quite literally able to drop off the radar. They to head to a location that will issue marriage licenses without waiting periods or blood tests, and Hilda suddenly decides that it’s time to do something she has considered for years and marry Professor Burroughs. After the wedding, the two pairs of newlyweds head for Jake’s vacation home, a secret off-the-grid mansion worthy of a villain from a James Bond movie. (How exactly he’s been able to afford this on a college math professor’s salary is left as an exercise for the reader.) Here Zeb and Hilda discover that not only has the professor been doing multi-dimensional math, but he’s developed a device that can travel between dimensions. It turns out the number of possible dimensions they can visit is six to the sixth power, and that sum increased to the sixth power again (when the number of the beast from the Book of Revelation, 666, is mentioned, someone speculates it may have been a mistranslation of the actual number). And soon Gay Deceiver is converted to a “continua craft” by the installation of the professor’s device. While I wasn’t familiar with Doctor Who when I first read the book, this time around I immediately recognized that Gay Deceiver had become a kind of TARDIS (which had made its first appearance on the series all the way back in 1963).

Heinlein is obviously having fun with this. There are many clear nods to pulp science fiction throughout the novel, starting with the character names (“Burroughs,” “John Carter,” “Dejah Thoris”) and their connection to Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom books. The story is told through the alternating voices of the four main characters, but this literary device is not very successful, as the grammar and tone is unchanged between sections; even with the names of the current viewpoint character printed at the top of the page, it is often difficult to determine whose viewpoint we are reading. The narrative incorporates the pronounced sexual overtones that mark Heinlein’s later work, and the banter between the four would today be grounds for a “hostile work environment” complaint in any place of business in the country. They even program Gay Deceiver, who has no choice in the matter, to speak in the same unsavory manner. The women have that peculiar mix of competence and submissiveness so common in Heinlein’s work. There is also sexual tension between pretty much every character except (mercifully) Deety and her father. They adopt a nudist lifestyle at Jake’s place, and Deety’s breasts and their attractiveness are mentioned so frequently that I started thinking of them as the fifth and sixth members of the expedition.

Their idyllic stay at Jake’s house is interrupted by a visit from a Federal Park Ranger. The men—who happen to be wearing their ceremonial military swords for fun—get a bad feeling and cut the ranger down, only to discover that he is an alien being disguised as a human, whom they dub a “Black Hat.” They suspect that he was an emissary of the forces behind the car bomb at Hilda’s house, and decide they better leave. That departure turns out to be just in time, as Jake’s house is promptly destroyed by a nuclear weapon. They flit between alternate dimensions and decide to experiment with space travel, heading toward a Mars in another dimension, which Hilda jokingly dubs “Barsoom.” They find the planet, which has a breathable atmosphere, inhabited by imperialist Russian and British forces. While Zeb is initially in charge, there is bickering among the intelligent and headstrong crew, and they decide to transfer command between themselves. This produces even more difficulties, and the bulk of the book is a tediously extended and often didactic argument mixed with dominance games, only occasionally interrupted by action. The four discover that the British have enslaved a native race—one that resembles the Black Hat creatures in the way a chimpanzee resembles a human. The crew helps the British stave off a Russian incursion, but decide to head out on their own. The only thing that drives the episodic plot from here on, other than arguments about authority and responsibility, is the fact that Hilda and Deety realize they are both pregnant, and have only a few months to find a new home free of Black Hats and where the inhabitants possess an advanced knowledge of obstetrics. They travel to several locations, many of which remind them of fictional settings, even visiting the Land of Oz. There Glinda modifies Gay Deceiver so she is bigger on the inside, further increasing her resemblance to Doctor Who’s TARDIS. They also visit E. E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensman universe, a visit cut short because Hilda has some illegal drugs aboard Gay Deceiver, and fears the legalistic Lensmen will arrest and imprison them.

Then the narrative becomes self-indulgent as it [SPOILERS AHEAD…] loops back into the fictional background of Heinlein’s own stories, and Lazarus Long arrives to completely take over the action, to the point of having a viewpoint chapter of his own. Jake, Hilda, Zeb, and Deety become side characters in their own book. The threat and mystery of the Black Hats is forgotten. Lazarus needs their help, and the use of Gay Deceiver, to remove his mother from the past so she can join his incestuous group marriage, which already includes Lazarus’ clone sisters. I had enjoyed Lazarus Long’s earlier adventures, especially Methuselah’s Children, but this soured me on the character once and for all. And you can imagine my disappointment when another subsequent Heinlein novel, The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, after a promising start, was also taken over by Lazarus Long…

The Pursuit of the Pankera

The new version of the story opens with essentially the same first third as the previously published version. When the four travelers arrive on Mars, however, they find they are on the actual world of Barsoom.

Buy the Book

The Pursuit of the Pankera

They encounter two tharks, who both have strong lisps. This is not just intended to be humorous; it makes sense because of the huge tusks Burroughs described in his books. Heinlein’s delight in revisiting Burroughs’ Barsoom is palpable. It has been some years since John Carter first arrived, and he and Tars Tarkas are off on the other side of the world, fighting in less civilized parts of the planet. In his absence, Helium is ruled by a kind of triumvirate composed of Dejah Thoris, her daughter Thuvia, and Thuvia’s husband Carthoris. The Earth has developed space travel, and there are tour groups and private companies like American Express with a presence in Helium. The four protagonists discover that there was a Black Hat incursion of Barsoom at some point, which was defeated. The creatures they call Black Hats, and the Barsoomians call Pankera, are now extinct on Mars. The four find that not only are the human companies exploiting the locals, but the Earth in this dimension is infested with Pankera. They decide to share Jake’s invention with the Barsoomians, with hopes that sharing the continuum secret will give Barsoom a fighting chance both in throwing off the economic exploitation of the earthlings, and also in defeating any further Pankera efforts to infiltrate or attack Mars. And then the four adventurers must leave, because Hilda and Deety are pregnant, and Barsoom is not an ideal place to deliver and raise babies (the egg-laying Barsoomians knowing little about live births).

The four then flit between several dimensions, including Oz, in a segment that again mirrors the original manuscript. But when they arrive in the Lensman universe, they stay for a while, have some adventures, and warn the Arisians about the threat of the Pankera. Like the section on Barsoom, Heinlein is obviously having fun playing in Smith’s universe and putting his own spin on things. As with John Carter, Heinlein wisely leaves Kimball Kinnison out of the mix, using the setting but not the hero. The four travelers do not want to have their children in the Lensman universe, which is torn by constant warfare with the evil Eddorians, so they head out to find a more bucolic home.

I won’t say more to avoid spoiling the new ending. I’ll just note that while reading The Pursuit of the Pankera, I kept dreading a re-appearance of the original novel’s ending, with Lazarus Long showing up and taking over the narrative. Long does appear, but in a little Easter Egg of a cameo that you wouldn’t even recognize if you don’t remember all his aliases. In contrast with The Number of the Beast, and as is the case with so many of my favorite books, the new ending leaves you wanting more and wondering what happens next.

Final Thoughts

Sometimes when manuscripts are discovered and published after an author’s death, it is immediately apparent why they had been put aside in the first place, as they don’t measure up to the works that did see the light of day. Sometimes they are like the literary equivalents of Frankenstein’s monster, with parts stitched together by other hands in a way that doesn’t quite fit. In the case of The Pursuit of the Pankera, however, the lost version is far superior to the version originally published. It is clear where Heinlein wanted to go with his narrative, and there is vigor and playfulness in the sections where the protagonists visit Barsoom and the Lensman universe, qualities I found lacking in The Number of the Beast. The sexual themes in the newly discovered sections are mercifully toned down, as is the perpetual bickering over command authority. And the newly published version continues to follow its four protagonists right to the end, instead of being hijacked by another character’s adventures.

And now I’ll stop talking, because it’s your turn to join the discussion: What are your thoughts on both the original book, and (if you’ve read it) on the newly published version? Did the new book succeed in bringing back the spirit of Heinlein’s earlier works?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

Didn’t like Number of the Beast much but the earlier draft sounds interesting.

Gharlane of Eddore’s Usenet post on The Number of the Beast changed the way I read the book forever. I’m not sure I like it any better, but it’s different.

https://www.heinleinsociety.org/2013/01/the-number-of-the-beast/

As a Heinlein fan for many years. And having not read The Number of the Beast. I now beleive I should and follow it on with The Pursuit of the Pankera.

I was intrigued by the conceit behind the multiple universes and how “fictional” universes were just as real as the “real’ universe is. Of course, that was about the time I was discovering the concept of crossover fiction so this fit right in. I was able to sufficiently gloss over the icky sexual parts and tedious bickering bits to confine my enjoyment to the adventures among the universes and how Heinlein tied in all his books into one meta-book.

But upon re-reading lo, these many years later, I discovered that not only had the suck fairy visited the book, but that she must have been having an extra-awfully bad day, because wow, did she ever hit it hard.

I haven’t read Pankera, but your review does tempt me.

Ah, thought I might be the first to mention Gharlane of Eddore’s post, but I see I’ve been beaten to the punch only two comments in!

@2 and @5 I was not aware of “Gharlane of Eddore” and his thoughts on The Number of the Beast, and found his take quite interesting. But if providing a critical writing primer mixed with a fictional tale was indeed Heinlein’s intent, in my opinion, the mélange didn’t work. The Pursuit of the Pankera works much better, because it celebrates the works of authors he liked, and that joy shows throughout.

Was it Jo Walton who recommended “No Heinlein over an inch thick.”? Because, yeah, Number is awful. I read it all the way through, once.

The first part of Time Enough was decent, and I reread that several times, but once the twins showed up I left. And Cat, well, I never got through that one.

It’s been a damn sight, but I’m pretty sure Jake and Deety do indeed end up fucking in this one. I’m positive that Deety and Hilda at least talk about it.

I’ve always suspected that Heinlein got so sex-obsessed with his later novels because he thought that was what made Stranger so successful.

As an unabashed Heinlein fan, I have read everything I could get my hand on, to the point that. while visiting the Library of Congress as a 17-year-old in 1966 I headed straight for the card catalog (remember those?) to look up every title Heinlein had published, something not easily available in very pre-Internet days. While I enjoyed parts of Number of the Beast, I did grow weary with the overlong who-should-be-in-charge squabble.

If you have shied away from Number of the Beast, don’t miss the opportunity to read The Pursuit of the Pankera. It is, indeed, infinitely superior, avoids most of the squabbling, and has what i think of as a most satisfactory ending, i.e., yearning for more. This is the Good Stuff – go get it.

When I first saw that Pankera had come out, I first wondered if it was click bait, or a scam. Then, I went to Amazon, found out it really was a NEW HEINLEIN NOVEL!!!!!!!!!!!!! and immediately ordered it for my kindle!

Not disappointed. I definitely took things into a different direction. LL is definitely just a minor character, and enjoyed the Lensmen portion! ( My game name is Kim Kinnison…)

Ahh, if only there was more.

I always enjoyed Number of the Beast; and it convinced me I needed to read both Smith and Dickson; so bonus points there. I’ve purchased PotP from Audible and it’s near the top of my queue. I look forward to it.

I have a high tolerance for Heinlein-isms but even I had trouble with the last section of NotB. It starts off fine as a pulp-ish adventure and I liked the Edwardian Mars. As a fan of ERB, Doc Smith and Baum’s Oz I was always a little disappointed that we didn’t really get to play much in those universes. Oz especially is a disappointing as there is little delight in it, and though Gay Deceiver is supposedly a kind of anthropomorphic machine while there, we as readers don’t really get to witness it.

It’s not only the bickering about authority that gets to me (which we have in plenty of other Heinlein), its the weird obsession with programming Gay. It’s like Heinlein just got his first 8-bit personal computer and worked it into his novel. All the programming bits are boring and don’t really play any important part in the story, other than when the women added extra canned responses that Gay could use.

Then characters from assorted Heinlein stories show up and everything really goes off the rails. The ending was supremely anti-climactic for me.

I’m not generally a fan of posthumously completed works, but I might actually pick this up as it sounds like it has more of the parts I liked about NotB and less of the parts I didn’t like.

Yeah, definitely agree that Pursuit of the Pankera is better than the version published as Number of the Beast back in the 80s. I agree with your suspicion that it might have been rights issues that sunk the original version of Pankera. If so, the culprit may have been Burroughs more than Smith, as Doc Smith and the Smith estate have on occasion been willing to agree to use of Smith’s characters in other works (Ellern’s New Lensman, Kyle’s The Dragon Lensman and sequels, Ryk Spoor’s Arena novels).

I grew up on Heinlein’s juveniles and have read and enjoyed – to one degree or another – pretty much everything he ever wrote up until Number of the Beast. That’s where he lost me. The only book after that that I really enjoyed was Friday. I’ll probably give The Pursuit of the Pankera a try at some point I guess but I’m not terribly enthusiastic about it.

I seem to recall Heinlein having some cerebrovascular problems in the late 70s/early 80s. Was The Pursuit of the Pankera written before or after this?

Have to agree with you on the obsession with Deety’s endowments, but even so, I thought that line about her being the sole support of two dependents was rather clever.

I read NotB quite some time ago and just finished reading PotP. They both have their good points and I missed some of the humorous dialogue that didn’t make it into PotP. I’ve read most of Doc E. E. Smith’s work and I own all of Edgar Rice Burroughs John Carter of Mars series. Thuvia is NOT DejahThoris’s daughter…she is her DIL, being married to Carthoris, her son, whose name comes from a combining of John CARter and Dejah THORIS. Dejah Thoris’s daughter’s name is Tara. I enjoyed both books for various reasons. I do have to give PotP the edge as it is more of a planned out story with a decisive end and more direction and reason for the places they visited. NotB really is more of a “romp” without direction. They say not to include anything in your novel that doesn’t move the story forward. The whole Edwardian Mars visit does little to move the story anywhere. Woodrow Wilson Smith aka Lazarus Long can be a bit of a pill and as one of the other characters commented: “He had to be the bride at every wedding”, so yes, he does take over that section of the book rather clumsily. I do love RAH’s writing and have read most of his juveniles, which I own and adore. I’ve read most of his adult books and enjoyed those as well.

I also was a Heinlein fan for many years but was really surprised by how much I disliked his later novels. I’m very glad to hear that The Pursuit of the Pankera seems to have avoided the issues that troubled me, and I’m looking forward to reading it. Thank you.

Just a reminder of our commenting guidelines: you’re welcome to disagree with the original article or other commenters, but don’t be rude or make your criticisms personal. The full moderation policy can be found here.

@16 Thanks for the correction on Thuvia. While I recently re-read A Princess of Mars, I haven’t read Thuvia’s adventures since about 50 years ago, and my recall just ain’t what it used to be.

Thanks for the extensive review that is fair, for those who dislike the latter Heinlein novels.

When I purchased The Number of the Beast when it first came out I was extremely disappointed. Constant squabbling mainly over who was in charge, almost random jumping around the universes as the main plot, too much writing about fiction and other writers. I don’t mind the sex but his female characters are an odd mix of strong, intelligent, and competent but with very high sex drives and too eager to be submissive to the right man.

I later saw the Gharlane post on reading the metafiction portions of TNotB and it improved my feelings about the book on rereading.

https://www.heinleinsociety.org/2013/01/the-number-of-the-beast

I have just started TPotP and it diverges nicely when they jump to other dimensional universes.

I read Number of the Beast while Heinlein was still alive. It was godawful then and I’m sure time has not improved it. Heinlein of that era was self indulgent, undisciplined, and sexually obsessed. Apparently he always was, but the 60’s liberated him from not writing about it.

I supported the crowdfunding and received my copy of the book a week or so ago. I began to read it, and found myself bogged down for the same reason as when I read the originally-published book: Four annoying characters who speak exactly alike, and at great and tiring length. I’ve put it aside temporarily to read another book that just arrived in the mail, but I do plan to go back to it when I’ve finished with that one.

I find most of Heinlein’s late novels to be problematic, to say the least, and have long since devised my own derogatory nicknames for them, to wit:

I Will Fear No Editor

Time Enough for a Nap

The Numbing of the Beast

The Cat Who Bores Through Walls

To Sail Beyond Endurance

Perhaps I’m not alone in thinking so?

Your titles are just perfect. I have read everyone of these books, but I’m not sure I can summon the endurance to put myself through Pankera.

I think I’ve moved on from Heinlein.

A review I wrote for DASFAx, the newsletter of the Denver Area Science Fiction Association:

WRITERS OF THE PURPLE PAGE:

The Pursuit of the Pankera: Solution Unsatisfactory?

By Sourdough Jackson

Last month, a new Heinlein novel came out, assembled from fragments found in his papers. The Pursuit of the Pankera contains no interpolations to link the fragments together; when placed in their correct order, they form a complete novel.

I awaited it with some trepidation, as pre-publication announcements stated this was, as its subtitle stated, “A Parallel Novel About Parallel Universes,” and the novel it paralleled was, alas, The Number of the Beast. I have little use for most of what Heinlein wrote after 1958, the exceptions being Stranger in a Strange Land and The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. I have a sentimental attachment to Podkayne of Mars, but I know full well that one was a dud, when compared to RAH’s earlier work.

Despite my fondness for alternate-history tales, I found long ago that Number was easily Heinlein’s worst book. Pursuit turned out to be somewhat better, but it still has serious flaws. Something the editor did, as a service to the reader, was to place a discreet marker in the margin, near the top of page 152, where the two novels diverge—the first thirty percent is virtually identical to the original.

This means slogging through the same initial sequence, and getting to know the four main characters again, none of whom resonate with me. Jake Burroughs, his daughter Deety, Zeb Carter, and Hilda Corners are hyper-competent geniuses, deadly opponents in any fight, and arrogant as all hell.

Their origin is an Earth similar to ours, in what is apparently the early 21st century—flying cars are common. The elder Burroughs discovers the theory and practice of paratime travel. As in Number, they have little common sense to go with their brains; while escaping from an attempt on all their lives, they take time out to marry in a great deal of haste (Jake with Hilda, Zeb with Deety).

Still on the run, they honeymoon in Jake’s desert hideout, with a romantic interlude that could’ve been handled better. I tired quickly of the sexual banter; as in most of his late-period novels, Heinlein overdid it. Like Tabasco sauce, a little of that stuff goes a very long way.

During that time, Jake refits Zeb’s flying car to function as a “continua craft,” meaning “paratime machine.” It has sufficient life support to handle space; it’s unclear to me whether this was original equipment. Then they’re interrupted by a “federal ranger” who tries to arrest them, and whom they kill quickly. On inspection (and dissection), the “ranger” turns out to be an alien infiltrator. The two couples put this together with the earlier attempt on their lives, conclude that the aliens want to eliminate anyone who knows the truth about paratime travel, and bug out in a hurry. They attempt a trip to Barsoom, the alternate Mars created by Edgar Rice Burroughs.

This is the divergence point. In Number, they reach a Mars that looks like Barsoom, but isn’t, while in Pursuit, they find a real one. Once they meet the Barsoomians, and are welcomed to the city of Helium, Jake and Zeb discover an inconvenient truth. Their wives are pregnant, and they are honored guests on a planet that has no obstetricians, or even backwoods midwives. All Barsoomians are oviparous, meaning they know no more of obstetrics than we do of the healthy incubation and hatching of children.

In a museum, they find an ancient specimen of an extinct invader who matches the phony ranger they killed earlier. These beings were called Panki or Pankera by the green Barsoomians, and tradition informs them that the Pankera tasted very good when cooked. Apparently, the Pankera have infiltrated the local version of Earth, as there is another attempt to apprehend the party by Terran visitors (this Barsoom has minor commercial relations with Earth, mostly in the form of tourists).

They scram once more, and visit Oz. No obstetricians there, either—childbirth is an alien concept, but for different reasons from Barsoom’s—but Glinda the Good does refit their flying car with a new interior, somewhat similar to that of a TARDIS (as also happens in Number). Eventually, they wind up in Doc Smith’s Lensman universe, and have some interesting times there.

The ending is one of the things that really gripes me about this book. No spoilers, but Heinlein has used this kind of ending before, in The Puppet Masters and Starship Troopers, two of my least-favorite books of his. The only good thing about it is that he doesn’t throw in Lazarus Long, except as an offstage cameo (in Number of the Beast, we see entirely too much of that ancient no-account).

The real problem with Pursuit isn’t the ending, though, or the insipid sexual banter that he habitually overused in his old age. It is the attitudes of the protagonists. I don’t call them “heroes,” as they don’t act very heroic, in my opinion.

Due to two murder attempts coupled with two attempts at imprisonment (which might or might not have been disguised murder attempts), the four not-heroes infer that all the Pankera are intent on killing them, and on enslaving every variant of Earth they contact. Their response, once they are settled somewhere comparatively safe and resolve their obstetrics problem, is to hunt and kill the Pankera whenever and wherever in the Multiverse they find them. The term they use for a version of Earth that has been infiltrated by Pankera— “infested”—says a lot about the Burroughses and the Carters, none of it good.

There is no attempt at any point to analyze why the Pankera might be after them, other than to prevent Jake Burroughs from further development or publication of his findings about paratime. Their motive might be a takeover of Earth, or it might simply be to protect “the Paratime Secret,” similar to the mission of the Paratime Police in some of H. Beam Piper’s stories. Bear in mind that, in Piper’s tales, it’s the good guys, not the villains, who preserve that secret.

Late in the tale, they survey many alternate Earths, and find ten of them to be “infested.” The worst case is our own world—it’s easy enough to figure this out from the clues Heinlein gives. Their solution to this problem is unethical in the extreme: extermination. If it proves impossible to root out all the Pankera from a particular Earth, the entire planet is to be burnt off.

This is the attitude of Cato toward the Carthaginians, of Hitler toward the Jews (and Roma, and Slavs, etc.), and of far too many immigrants to the New World toward the Native Americans.

This is also, alas, an attitude taken by many of the early authors of science fiction, especially of space opera. Don’t just beat the invading problem, followed by negotiating a peace with it, destroy it utterly! Root and branch! Vermin of the Universe! The only good _______is a dead _____!

Doc Smith, for all that I loved his tales, was a cardinal sinner here. I think “nuance” was a word in a foreign language (French?) to most of science fiction’s pioneers.

Some didn’t glorify genocide in their sagas—Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Arthur C. Clarke come to mind. Thankfully, by the 1950s and 1960s, SF had rid itself of much of this nonsense. Absent from Star Trek were aliens who acted like Smith’s Osnomians or the humans in Starship Troopers. Captain Kirk (and later, Captains Picard and Sisko) didn’t try to destroy all Klingons, Romulans, or Cardassians.

One would think that, by 1980, Heinlein might have gotten the message. In 1945, after all, he and the rest of the world discovered the crimes of the Nazis and the Japanese militarists. And yet, he and some others continued to propose extermination as a solution to the problem of unfriendly aliens. One might think Heinlein was channeling the Daleks. Containment, the strategy that finally won the Cold War, never seemed to enter his head, at least when he was writing a novel.

Or, perhaps, he did get the message—The Number of the Beast, for all its manifold faults, is what got published in 1980, not The Pursuit of the Pankera. In Number, the trouble made by the (unnamed in that book) Pankera is dismissed by Jubal Harshaw as having been directly caused by a single entity, the one who was killed at Jake’s hideout. The real troublemaker, who tries to crash the convention at the end of Number, falls from a great height as it charges up Bifrost to storm Asgard—and the Rainbow Bridge vanishes underneath it.

It’s entirely possible that Pursuit was the original draft, and Number was the second—rewritten after Heinlein realized the ethical mess he’d created.

Pursuit is for Heinlein completists (I am one). Don’t expect anything like his average work during his middle period, much less such gems as The Door into Summer or Have Space Suit—Will Travel.

My nutshell assessment of The Pursuit of the Pankera comes from Heinlein himself:

Solution unsatisfactory!

PotP is a much more straightforward SF novel than NotB, but suffers from Heinlein’s pointless fan fiction about Barsoom and the Gray Lensman universe, neither of which does much to advance the plot. And without much of the (often melodramatic) leadership conflict that was added into NotB, the novel as a while turns into a largely conflict-free SF travelogue by a quartet of uber-people.

Neither is a very good novel — NotB is probably more interesting, net-net, but in incredibly goofy ways. If I had to recommend one or the other to a friend, it would be PotP, but I’d probably point them instead to any number of other Heinlein books.

On the other hand, whether PotP is a “good” book or not, Lensman and Barsoomian fan-fic written by Heinlein sounds incredibly interesting to me.

I enjoyed your review having just finished PoP ( easier than pecking it out).

Two quibbles, 1) both books explain in detail how Jacob, indeed all of them, got their money. It was not from being a College Professor.

2) On Batsoom, Cart is Deja Thoris’ son and Thuvia the daughter in law.

#25 Sourdough Jackson:

Thank you for the review. The genocidal ending is bad for a number of reasons. Even from ta rational and prudent point of view that lacks empathy, going in to kill an enemy with so little knowledge of their resources, organization, and plans seems insane. Also, the idea of sterilizing human-inhabited planets which don’t do a good enough job of wiping out Pankera is horrendous.

A more thorough look at the implications of the multiverse would have led to the idea of infinite numbers of Gay Deceivers and their crews, which would have resulted in a very abstract conflict. And have fun figuring out the command structure.

In Heinlein’s Have Space Suit, Will Travel, the Three Galaxy Council decides to rotate the Wormface planet. Tilt it ninety degrees outside normal space time. Leaving their local star behind.

They came within ames-ace of doing the same thing to Earth.

Even classic Heinlein dealt in genocide.

@@@@@ 28, NancyLebovitz:

A more thorough look at the implications of the multiverse would have led to the idea of infinite numbers of Gay Deceivers and their crews, which would have resulted in a very abstract conflict. And have fun figuring out the command structure.

In the first of his Paratime stories, H. Beam Piper posited multiple Paratime Police on multiple timelines. That was retconned out of the rest of the series.

Me I quite liked Pankera. An enjoyable and intimate romp, even if the characters are somewhat over the top. I enjoy recognizing the Heinleinisms -rephrasings of Lazarus Long’s aphorisms, spanking, nudism, authority quibbles, hospitality, honor, it’s all there.

Now I’m reading Beast to compare – page by page. It turns out the first third is NOT quite the same, Pankera is a slightly shortened version, with all of the most offensive bits edited out! Deety’s insecurity about her body odor, the flirtation between Zeb and Hilda, Deety’s confession she would have had sex with her father if only he’d asked, the crudest references to sex, the nipples going spung!, and more.

I’m so curious why! Did Heinlein so instruct, or did the editor decide these edits were necessary for continuity of style? For the rest of Pankera is milder than Beast. Even the word teat occurs only once…

Regarding the reviewer’s comment “(How exactly he’s been able to afford this on a college math professor’s salary is left as an exercise for the reader.)”, perhaps his version was somewhat abridged as Deety tells Hilda that Jake has been inventing things like “a hen lays eggs”, and the profits from those inventions trickle back in various ways.

Alan, thank you for your reviews of both books. I started reading SF in my teens in the seventies and read most of Asimov’s, Clarke’s and Heinlein’s works, among others. However, I was (and still am) a romantic and I truly enjoyed Heinlein’s works that included romance even though in many of his juveniles the protagonist gave up the girl for exploration. For whatever reasons, I never read Stranger in a Strange Land, I Will Fear No Evil or Time Enough for Love. So, 1980 rolls around, I turned 18 and The Number of the Beast is published in the new trade paperback format, which I bought (I have the same edition you have).

The story started out with romance (at least of a sort), which I liked (and being 18 I probably hoped that it would be that easy to meet a girl!) and the action started shortly after. So far so good, but after arriving on Mars I felt the story started to stall between the in depth mathematics and bickering between the four main characters. Worst of all for me, I had just read the first 6 Burroughs Mars books the year before when Ballantine/Del Rey had republished them with the gorgeous Michael Whelan covers (my favorite cover artist), so I was very disappointed that the Mars in the book was 19th century Russian and English colonies. Together that caused me to stop reading the book and never finish it. Despite this I bought Friday, which I liked and finished, JOB: A Comedy of Justice, which I tried to like and The Cat Who Walked Through Walls, which I didn’t like and also never finished.

So, when I learned that The Pursuit of the Pankera was supposed to be closer to the older Heinlein stories I bought it. I was able to finish it and found it somewhat enjoyable. I also liked the visit to Prime Base, as I read the Lensman series in the eighties. I even had a much better grasp of OZ since I had also read the first 6 OZ books to my daughter when she was little. As some of the other comment mention, there are issues with the story. Even Heinlein points out the problem of just walking away from Gay Deceiver in The Number of the Beast, but I think almost any SF story has problems that are ignored but can be easily spotted if you look for them. In fact, I found the biggest problem with the story is that there is no real tension for the whole time our protagonists are on Barsoom or at Prime Base. Both of those stops are pretty much just Heinlein getting to play in the Burroughs Mars and Doc Smith Lensman universes, but without any danger (and in the case of Helium some jarring capitalism tossed in). Also, I felt the ending of the book was tacked on and rushed. So, overall I don’t think it’s one of Heinlein’s best works, but I do think it’s still worth reading.

Which brings me back to The Number of the Beast. After finishing PotP I decided to read (and finish) it so I could actually compare the two works. Of course I’m coming at it from a completely different point of view as I was a teenager when I first started to read it and now I’m older than Jake. I don’t think that made much of a difference as I’m still a romantic all these years later. I found the bickering among the four leads like them much less than I did in PotP (which had some bickering as well, but not to the same extent). I also noticed that in the reception scene at Glinda’s palace in OZ Jake still says, “You put it neatly, Professor. I wish Professor Mobyas Toras could hear your formulation.” (the bottom of page 336 of my trade paperback edition). Meaningless to anyone reading The Number of the Beast before The Pursuit of the Pankera was published. He is mentioned again in the last chapter, which I suppose might have confused anyone who noticed. I also think the ending of NotB is also tacked on and much worse than the ending of PofP.

In The Pursuit of the Pankera Heinlein mentions What Mad Universe by Fredric Brown regarding parallel universes (page 203). As I had first read many of Brown’s short stories in The Best of Fredric Brown and I enjoyed his writing I put What Mad Universe on my to read list after The Number of the Beast. I just finished reading it and I found it to be a much better story than either PotP or NotB: tightly written and/or edited, fast-paced and with tension throughout. It was also interesting to note that Heinlein using a sewing machine as the continua device was probably in homage to Brown’s instantaneous space travel device. However, Heinlein apparently disagreed with Brown about the effect of sudden materialization in air. I recommend What Mad Universe highly to anyone who has read either of the two Heinlein works.

@35,36 Thanks for your thoughts. TPOTP is not among Heinlein’s best works, but it is a lot better than TNOTB, and even mediocre Heinlein is better than most other SF. By the way, is Lucas Trask your real name, or are you a Space Viking fan?

Alan, thanks for your reply. Yes, I’m a Space Viking and H. Beam Piper fan. He is #2 on my list of favorite SF authors, just behind Lester del Rey. Heinlein is third, just ahead of Asimov and Clarke. I agree that mediocre Heinlein is better than most other SF, but I also believe that his strongly edited works are much better then his weakly edited works.

@39 No writer is better without editorial guidance! ;-)

(How exactly he’s been able to afford this on a college math professor’s salary is left as an exercise for the reader.)

Deety: “Now about how Pop got rich — All the time he’s been teaching he’s also been inventing gadgets — as automatically as a hen lays eggs. A better can opener. A lawn irrigation system that does a better job, costs less, uses less water. Lots of things. But none has his name on it and royalties trickle back in devious ways.“

I stand corrected…